Translate

Monday, 24 November 2014

Friday, 21 November 2014

Cases of Ebola Diagnosed in the United States

- October 23, 2014 - The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reported a case of Ebola in a medical aid worker who had returned to New York City from Guinea, where the medical aid worker had served with Doctors Without Borders.

- The diagnosis was confirmed by CDC on October 24.

- The patient has recovered and was discharged from Bellevue Hospital Center on November 11.

- October 15, 2014 – A second healthcare worker who provided care for the index patient at Texas Presbyterian Hospital tested positive for Ebola.

- This second healthcare worker was transferred to Emory Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia.

- The healthcare worker had traveled by air from Dallas to Cleveland on October 10 and from Cleveland to Dallas on October 13. CDC worked to ensure that all passengers and crew on the two flights were contacted by public health professionals to answer their questions and arrange follow up as necessary.

- The patient has since recovered and was discharged on October 28.

- By November 3, all passengers on both flights completed the 21-day monitoring period.

- October 10, 2014 – A healthcare worker at Texas Presbyterian Hospital who provided care for the index patient tested positive for Ebola.

- The healthcare worker was isolated after the initial report of a fever and subsequently moved to the National Institutes for Health (NIH) Clinical Center.

- The patient has since recovered and was discharged on October 24.

- September 30, 2014 – CDC confirmed the first laboratory-confirmed case of Ebola to be diagnosed in the United States in a man who had traveled to Dallas, Texas from Liberia.

- The man did not have symptoms when leaving Liberia, but developed symptoms approximately four days after arriving in the United States.

- The man sought medical care at Texas Presbyterian Hospital of Dallas after developing symptoms consistent with Ebola. Based on his travel history and symptoms, CDC recommended testing for Ebola. The medical facility isolated the patient (i.e., index patient) and sent specimens for testing at CDC and at a Texas laboratory.

- Local public health officials identified all close contacts of the index patient for daily monitoring for 21 days after exposure.

- The patient passed away on October 8.

- By November 7, all contacts of the patient completed the 21-day monitoring period.

CDC recognizes that any case of Ebola diagnosed in the United States raises concerns, and any death is too many. Medical and public health professionals across the country have been preparing to respond to the possibility of additional cases. CDC and public health officials in Texas, Ohio, and New York are taking precautions to identify people who had close personal contact with the patients, and healthcare professionals have been reminded to use meticulous infection control at all times.

2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa - Outbreak Distribution Map

Countries with Cases of Ebola

| Countries with widespread transmission1 | Affected areas |

|---|---|

| Guinea | Entire country |

| Liberia | Entire country |

| Sierra Leone | Entire country |

| Countries with an initial case or cases and/or localized transmission | Affected areas |

|---|---|

| Mali2 | Kayes, Kourémalé, and Bamako |

| United States3 | Dallas, TX, New York City |

| Previously affected countries4 | Affected areas |

|---|---|

| Nigeria | Lagos, Port Harcourt |

| Senegal | Dakar |

| Spain | Madrid |

Travelers arriving from all areas of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone are at risk for exposure to Ebola virus.

A single Ebola case was imported from Guinea and was diagnosed in Kayes, Mali on October 23, 2014; no further transmission was associated with this case. Investigation of localized Ebola transmission in Kourémalé and Bamako, following a separate importation from Guinea is currently underway.

One travel-associated Ebola case was imported from Liberia to Dallas, and resulted in transmission to two healthcare workers. One travel-associated Ebola case in a healthcare worker was imported to New York City from Sierra Leone, and did not result in further transmission. Travelers to Dallas or New York City are not at risk for exposure to Ebola.

These countries are currently Ebola-free.

One international importation of Ebola to Nigeria from Liberia resulted in localized transmission (20 cases and 8 deaths), which has ceased.

A single Ebola case in Senegal was imported from Guinea, and did not result in further transmission.

A single Ebola case occurred in a Spanish healthcare worker caring for an Ebola patient who had been transported to Spain from Liberia for care, and did not result in further transmission.

Travelers to Nigeria, Senegal, and Spain are not at risk for exposure to Ebola.

One international importation of Ebola to Nigeria from Liberia resulted in localized transmission (20 cases and 8 deaths), which has ceased.

A single Ebola case in Senegal was imported from Guinea, and did not result in further transmission.

A single Ebola case occurred in a Spanish healthcare worker caring for an Ebola patient who had been transported to Spain from Liberia for care, and did not result in further transmission.

Travelers to Nigeria, Senegal, and Spain are not at risk for exposure to Ebola.

Monday, 17 November 2014

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Ebola in a person who has been infected for only a few days is difficult because the early symptoms, such as fever, are nonspecific to Ebola infection and often are seen in patients with more common diseases, such as malaria and typhoid fever.

However, if a person has the early symptoms of Ebola and has had contact with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola; contact with objects that have been contaminated with the blood or body fluids of a person sick with Ebola; or contact with infected animals, they should be isolated and public health professionals notified. Samples from the patient can then be collected and tested to confirm infection.

Ebola virus is detected in blood only after onset of symptoms, most notably fever, which accompany the rise in circulating virus within the patient's body. It may take up to three days after symptoms start for the virus to reach detectable levels. Laboratory tests used in diagnosis include:

| Timeline of Infection | Diagnostic tests available |

|---|---|

| Within a few days after symptoms begin |

|

| Later in disease course or after recovery |

|

| Retrospectively in deceased patients |

|

Saturday, 15 November 2014

Epidemiologic Risk Factors to Consider when Evaluating a Person for Exposure to Ebola Virus

The following epidemiologic risk factors should be considered when evaluating a person for Ebola virus disease (Ebola), classifying contacts, or considering public health actions such as monitoring and movement restrictions based on exposure.

- High risk includes any of the following:

- Percutaneous (e.g., needle stick) or mucous membrane exposure to blood or body fluids of a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- Exposure to the blood or body fluids (including but not limited to feces, saliva, sweat, urine, vomit, and semen) of a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic without appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Processing blood or body fluids of a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic without appropriate PPE or standard biosafety precautions

- Direct contact with a dead body without appropriate PPE in a country with widespread Ebola virus transmission

- Having lived in the immediate household and provided direct care to a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- Some risk includes any of the following:

- In countries with widespread Ebola virus transmission:

- direct contact while using appropriate PPE with a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic or with the person's body fluids

- any direct patient care in other healthcare settings

- Close contact in households, healthcare facilities, or community settings with a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- Close contact is defined as being for a prolonged period of time while not wearing appropriate PPE within approximately 3 feet (1 meter) of a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- In countries with widespread Ebola virus transmission:

- Low (but not zero) risk includes any of the following:

- Having been in a country with widespread Ebola virus transmission within the past 21 days and having had no known exposures

- Having brief direct contact (e.g., shaking hands) while not wearing appropriate PPE, with a person with Ebola while the person was in the early stage of disease

- Brief proximity, such as being in the same room for a brief period of time, with a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- In countries without widespread Ebola virus transmission: direct contact while using appropriate PPE with a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- Traveled on an aircraft with a person with Ebola while the person was symptomatic

- No identifiable risk includes:

- Contact with an asymptomatic person who had contact with person with Ebola

- Contact with a person with Ebola before the person developed symptoms

- Having been more than 21 days previously in a country with widespread Ebola virus transmission

- Having been in a country without widespread Ebola virus transmission and not having any other exposures as defined above

- Aircraft or ship crew members who remain on or in the immediate vicinity of the conveyance and have no direct contact with anyone from the community during the entire time that the conveyance is present in a country with widespread Ebola virus transmission

Friday, 14 November 2014

Risk of Exposure

Ebola viruses are found in several African countries. Ebola was first discovered in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, outbreaks of Ebola among humans have appeared sporadically in Africa.

Ebola viruses are found in several African countries. Ebola was first discovered in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, outbreaks of Ebola among humans have appeared sporadically in Africa.Risk

Healthcare providers caring for Ebola patients and family and friends in close contact with Ebola patients are at the highest risk of getting sick because they may come in contact with the blood or body fluids of sick patients. People also can become sick with Ebola after coming in contact with infected wildlife. For example, in Africa, Ebola may spread as a result of handling bushmeat (wild animals hunted for food) and contact with infected bats. The virus also can be spread through contact with objects (like clothes, bedding, needles, syringes/sharps or medical equipment) that have been contaminated with the virus.

Past Ebola Outbreaks

Past Ebola outbreaks have occurred in the following countries:

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

- Gabon

- South Sudan

- Ivory Coast

- Uganda

- Republic of the Congo (ROC)

- South Africa (imported)

About Ebola Virus Disease

Ebola, previously known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a rare and deadly disease caused by infection with one of the Ebola virus strains. Ebola can cause disease in humans and nonhuman primates (monkeys, gorillas, and chimpanzees).

Ebola is caused by infection with a virus of the family Filoviridae, genus Ebolavirus. There are five identified Ebola virus species, four of which are known to cause disease in humans: Ebola virus (Zaire ebolavirus); Sudan virus (Sudan ebolavirus); Taï Forest virus (Taï Forest ebolavirus, formerly Côte d’Ivoire ebolavirus); and Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo ebolavirus). The fifth, Reston virus (Reston ebolavirus), has caused disease in nonhuman primates, but not in humans.

Ebola viruses are found in several African countries. Ebola was first discovered in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Since then, outbreaks have appeared sporadically in Africa.

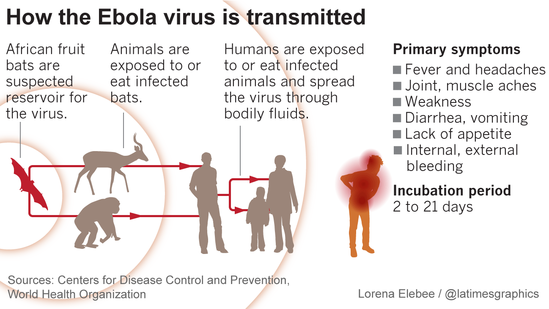

The natural reservoir host of Ebola virus remains unknown. However, on the basis of evidence and the nature of similar viruses, researchers believe that the virus is animal-borne and that bats are the most likely reservoir. Four of the five virus strains occur in an animal host native to Africa.

Transmission

Because the natural reservoir host of Ebola viruses has not yet been identified, the way in which the virus first appears in a human at the start of an outbreak is unknown. However, scientists believe that the first patient becomes infected through contact with an infected animal, such as a fruit bat or primate (apes and monkeys), which is called a spillover event. Person-to-person transmission follows and can lead to large numbers of affected people. In some past Ebola outbreaks, primates were also affected by Ebola and multiple spillover events occurred when people touched or ate infected primates.

When an infection occurs in humans, the virus can be spread to others through direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes in, for example, the eyes, nose, or mouth) with

- blood or body fluids (including but not limited to urine, saliva, sweat, feces, vomit, breast milk, and semen) of a person who is sick with Ebola

- objects (like needles and syringes) that have been contaminated with the virus

- infected fruit bats or primates (apes and monkeys)

Ebola is not spread through the air, by water, or in general, by food. However, in Africa, Ebola may be spread as a result of handling bushmeat (wild animals hunted for food) and contact with infected bats. There is no evidence that mosquitos or other insects can transmit Ebola virus. Only a few species of mammals (e.g., humans, bats, monkeys, and apes) have shown the ability to become infected with and spread Ebola virus.

Healthcare providers caring for Ebola patients and family and friends in close contact with Ebola patients are at the highest risk of getting sick because they may come in contact with infected blood or body fluids.

During outbreaks of Ebola, the disease can spread quickly within healthcare settings (such as a clinic or hospital). Exposure to Ebola can occur in healthcare settings where hospital staff are not wearing appropriate personal protective equipment.

Dedicated medical equipment (preferably disposable, when possible) should be used by healthcare personnel providing patient care. Proper cleaning and disposal of instruments, such as needles and syringes, also are important. If instruments are not disposable, they must be sterilized before being used again. Without adequate sterilization of instruments, virus transmission can continue and amplify an outbreak.

Once people recover from Ebola, they can no longer spread the virus to people in the community. However, because Ebola can stay in semen after recovery, men should abstain from sex (including oral sex) for three months. If abstinence is not possible, condoms may help prevent the spread of Ebola. Sexual transmission of Ebola has never been reported.

Ebola virus disease

Key facts

- Ebola virus disease (EVD), formerly known as Ebola haemorrhagic fever, is a severe, often fatal illness in humans.

- The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals and spreads in the human population through human-to-human transmission.

- The average EVD case fatality rate is around 50%. Case fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90% in past outbreaks.

- The first EVD outbreaks occurred in remote villages in Central Africa, near tropical rainforests, but the most recent outbreak in west Africa has involved major urban as well as rural areas.

- Community engagement is key to successfully controlling outbreaks. Good outbreak control relies on applying a package of interventions, namely case management, surveillance and contact tracing, a good laboratory service, safe burials and social mobilisation.

- Early supportive care with rehydration, symptomatic treatment improves survival. There is as yet no licensed treatment proven to neutralise the virus but a range of blood, immunological and drug therapies are under development.

- There are currently no licensed Ebola vaccines but 2 potential candidates are undergoing evaluation.

Background

The Ebola virus causes an acute, serious illness which is often fatal if untreated. Ebola virus disease (EVD) first appeared in 1976 in 2 simultaneous outbreaks, one in Nzara, Sudan, and the other in Yambuku, Democratic Republic of Congo. The latter occurred in a village near the Ebola River, from which the disease takes its name.

The current outbreak in west Africa, (first cases notified in March 2014), is the largest and most complex Ebola outbreak since the Ebola virus was first discovered in 1976. There have been more cases and deaths in this outbreak than all others combined. It has also spread between countries starting in Guinea then spreading across land borders to Sierra Leone and Liberia, by air (1 traveller only) to Nigeria, and by land (1 traveller) to Senegal.

The most severely affected countries, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia have very weak health systems, lacking human and infrastructural resources, having only recently emerged from long periods of conflict and instability. On August 8, the WHO Director-General declared this outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

A separate, unrelated Ebola outbreak began in Boende, Equateur, an isolated part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The virus family Filoviridae includes 3 genera: Cuevavirus, Marburgvirus, and Ebolavirus. There are 5 species that have been identified: Zaire, Bundibugyo, Sudan, Reston and Taï Forest. The first 3, Bundibugyo ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, and Sudan ebolavirus have been associated with large outbreaks in Africa. The virus causing the 2014 west African outbreak belongs to the Zaire species.

Transmission

It is thought that fruit bats of the Pteropodidae family are natural Ebola virus hosts. Ebola is introduced into the human population through close contact with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected animals such as chimpanzees, gorillas, fruit bats, monkeys, forest antelope and porcupines found ill or dead or in the rainforest.

Ebola then spreads through human-to-human transmission via direct contact (through broken skin or mucous membranes) with the blood, secretions, organs or other bodily fluids of infected people, and with surfaces and materials (e.g. bedding, clothing) contaminated with these fluids.

Health-care workers have frequently been infected while treating patients with suspected or confirmed EVD. This has occurred through close contact with patients when infection control precautions are not strictly practiced.

Burial ceremonies in which mourners have direct contact with the body of the deceased person can also play a role in the transmission of Ebola.

People remain infectious as long as their blood and body fluids, including semen and breast milk, contain the virus. Men who have recovered from the disease can still transmit the virus through their semen for up to 7 weeks after recovery from illness.

Symptoms of Ebola virus disease

The incubation period, that is, the time interval from infection with the virus to onset of symptoms is 2 to 21 days. Humans are not infectious until they develop symptoms. First symptoms are the sudden onset of fever fatigue, muscle pain, headache and sore throat. This is followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, symptoms of impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases, both internal and external bleeding (e.g. oozing from the gums, blood in the stools). Laboratory findings include low white blood cell and platelet counts and elevated liver enzymes.

Diagnosis

It can be difficult to distinguish EVD from other infectious diseases such as malaria, typhoid fever and meningitis. Confirmation that symptoms are caused by Ebola virus infection are made using the following investigations:

- antibody-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen-capture detection tests

- serum neutralization test

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- electron microscopy

- virus isolation by cell culture.

Samples from patients are an extreme biohazard risk; laboratory testing on non-inactivated samples should be conducted under maximum biological containment conditions.

Treatment and vaccines

Supportive care-rehydration with oral or intravenous fluids- and treatment of specific symptoms, improves survival. There is as yet no proven treatment available for EVD. However, a range of potential treatments including blood products, immune therapies and drug therapies are currently being evaluated. No licensed vaccines are available yet, but 2 potential vaccines are undergoing human safety testing.

Prevention and control

Good outbreak control relies on applying a package of interventions, namely case management, surveillance and contact tracing, a good laboratory service, safe burials and social mobilisation. Community engagement is key to successfully controlling outbreaks. Raising awareness of risk factors for Ebola infection and protective measures that individuals can take is an effective way to reduce human transmission. Risk reduction messaging should focus on several factors:

- Reducing the risk of wildlife-to-human transmission from contact with infected fruit bats or monkeys/apes and the consumption of their raw meat. Animals should be handled with gloves and other appropriate protective clothing. Animal products (blood and meat) should be thoroughly cooked before consumption.

- Reducing the risk of human-to-human transmission from direct or close contact with people with Ebola symptoms, particularly with their bodily fluids. Gloves and appropriate personal protective equipment should be worn when taking care of ill patients at home. Regular hand washing is required after visiting patients in hospital, as well as after taking care of patients at home.

- Outbreak containment measures including prompt and safe burial of the dead, identifying people who may have been in contact with someone infected with Ebola, monitoring the health of contacts for 21 days, the importance of separating the healthy from the sick to prevent further spread, the importance of good hygiene and maintaining a clean environment.

Controlling infection in health-care settings:

Health-care workers should always take standard precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (to block splashes or other contact with infected materials), safe injection practices and safe burial practices.

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Ebola virus should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact (within 1 metre) of patients with EBV, health-care workers should wear face protection (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles), a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Ebola infection should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)